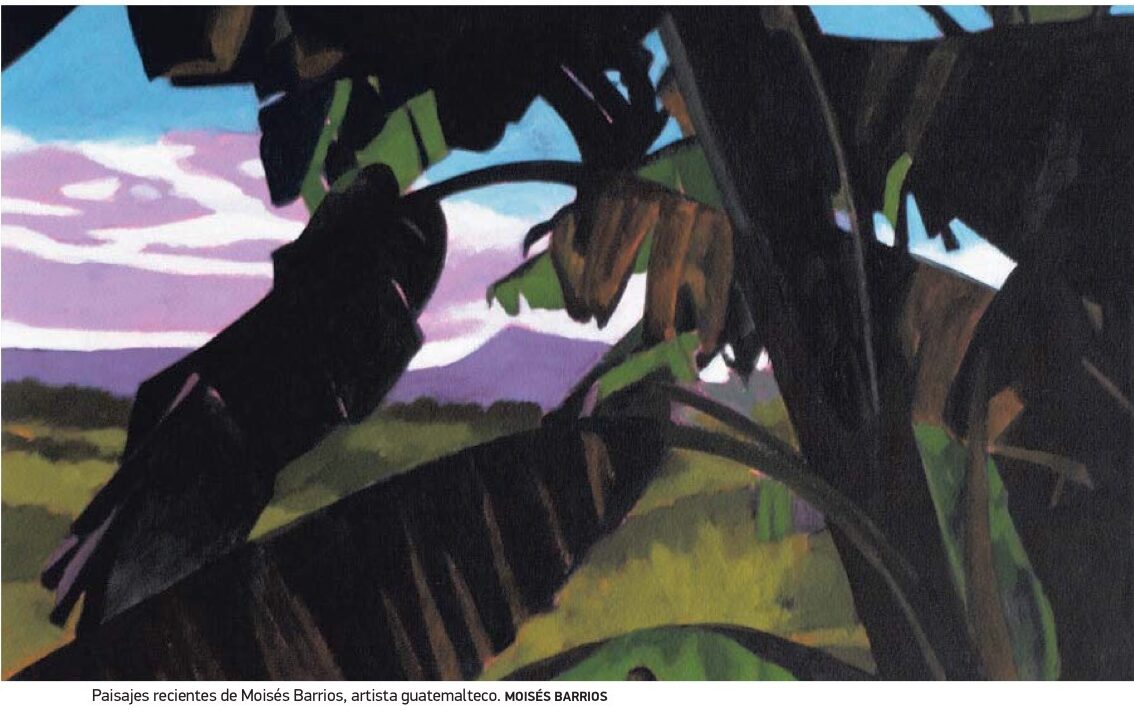

A few weeks ago, I visited visual artist Moisés Barrios in his studio in Guatemala City. Moisés showed me his most recent pictorial work and invited me to write a text to accompany his exhibition Paradisiaca.

In this text, I explore the main elements that are integrated into these works by the artist: volcanoes, paradise and bananas.

For many, the volcano is synonymous with destruction and punishment, of lava, incandescent rocks and ash clouds. He has earned that bad reputation because he behaves like the spoiled brat and the swindler of the party: he spits out his swear words when he feels like it and appears, more fired up than ever, when we thought he was quiet. This behavior seems to be the work of Lucifer himself. How else can we explain that a fiery flow descends the slope of a volcano, with the fury of a steamroller?

This is what happened in 79 AD, during the eruption of Mount Vesuvius, when a cloud of gas poisoned the population of Pompeii while it was sleeping. Then, a blanket of incandescent ash buried the bodies. The image of lovers sleeping in the eternal embrace is overwhelming, candid and horrifying.

Fertility

Our Central American landscape frequently exhibits its volcanoes. We have them short, flattened, conical, and iconic, or large and with complex structures, such as the Irazú, in Costa Rica. In general, our volcanoes are bullies. In Guatemala we have the Fire, which in 2018 killed about 200 people, and the Pacaya, which erupted violently in 1965 and has been in constant activity ever since.

Despite the destruction they cause, we are intimately linked to volcanoes. Ours is, if you will, a love-hate relationship: we hurt each other and then we reconcile. This happens because after the eruption, the components that drive fertility and life quickly emerge. Thanks to rain and heat, some minerals are transformed into clays that retain water and nutrients. Plants settle, grow, and reproduce.

Then the families arrive, who cultivate their slopes and establish themselves near the river where years before the incandescent flow passed. While our memory often fails, nature is wise: it conducts volcanic sediments through rivers and deposits them on flat ground. These sediments feed lush coastal landscapes reminiscent of paradise.

The forbidden fruit

Adam and Eve inhabit the paradise of the Central American coast. Imagine coconut water, white sand beaches, and torn sunsets. Everything is idyllic until, one day, a sweaty snake approaches them carrying the forbidden fruit in its mouth. It’s not red and crisp, but yellow and soft. It’s a banana.

That incident explains what will happen years later, when some greedy guys arrive with abacuses and theodolites to make calculations, to define where and how many hectares of the forbidden fruit will have to be planted. It is advisable to plant many, hopefully all the hectares, especially in the lowland areas, next to the coast, where temperatures are warm, soils fertile and humidity high.

Before planting, it is necessary to cut down the trees to take advantage of every inch of the territory. Toucans, butterflies and orchids matter little. Then will come engineers, who will recommend agrochemicals to improve crop yields and protect them from pests, diseases and weeds, bringing with them even more destruction.

Glitter and questions

In his paintings, Moisés Barrios depicts a lost paradise that, perhaps, has not completely disappeared. On its bunches of bananas sprout tropical flowers that do not give up, that survive despite everything. Those flowers shine against a dull background. The majestic sunsets also shine, the land of the ravines where wild species of bananas grow and the imperturbable sky.

All this contrasts with the advertising postcards designed and distributed by the banana companies to sell their products. These postcards strengthened the imagery that prevails over the tropics, populated abundantly by perfectly yellow fruits, colorful birds and women dressed in their dresses and dazzling smiles. The perfect yellow on postcards is identical to that of the bananas displayed on supermarket shelves in Miami.

In the distance, in the paintings of Moisés, the Pacaya volcano can be seen. From that distance he seems to ask us why the coastal forest has disappeared. Why, after having sent so many sediments, so many nutrients, after so much diverse and majestic jungle, today only the green plants of the forbidden fruit inhabit that land? As with the art that proposes and moves, the work of Moisés Barrios is a territory strewn with questions.