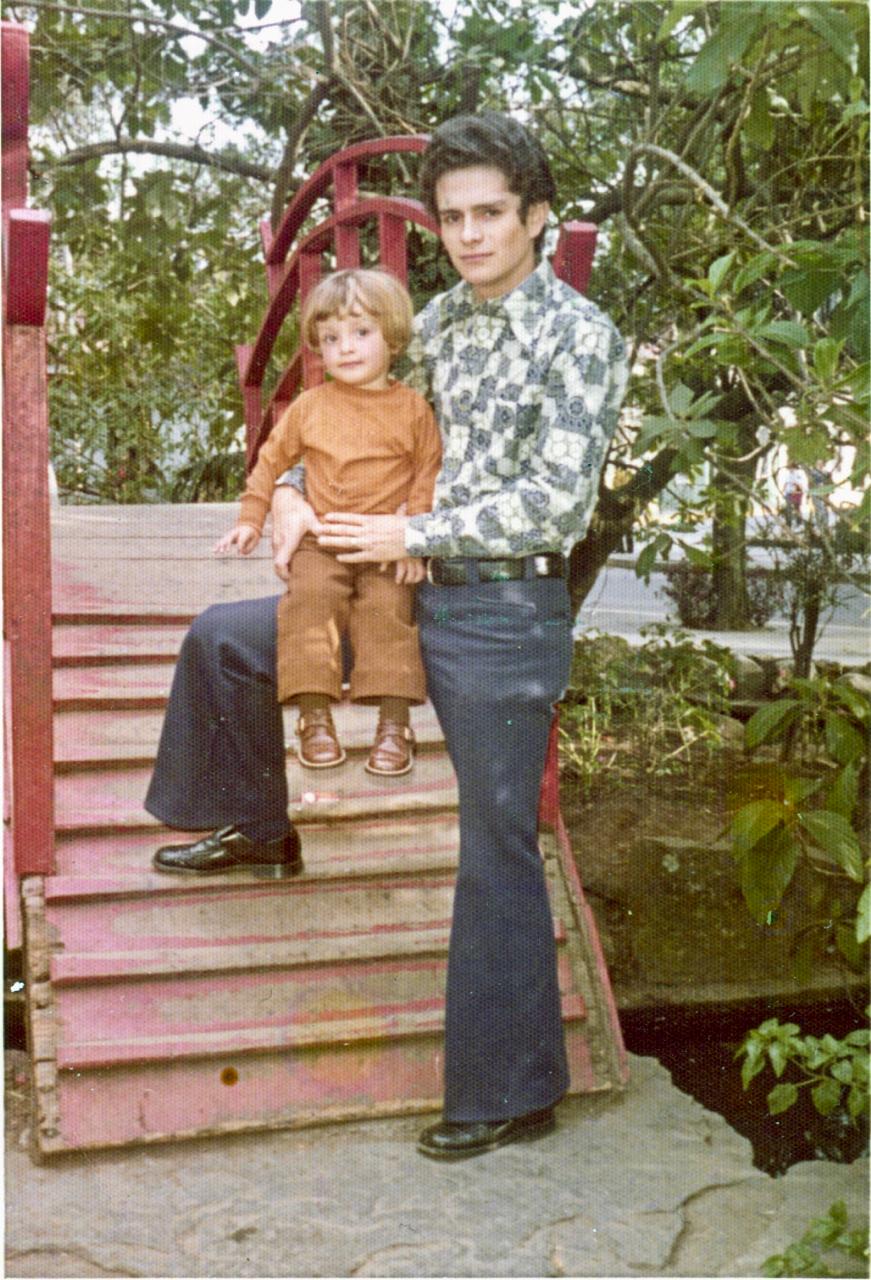

I remember the red bridge in Parque Chino. I remember it because, during my childhood, I climbed his hunchbacked back like someone climbing a mountain. Also, because it appears in a photograph that my mother took in 1976. In that photo, my dad rests his right leg on the bridge while I balance on his lap. He was twenty-four years old, and I was three.

Daniel Oduber was the president of Costa Rica in 1976. Today his monument throws proclamations to an imaginary crowd around Parque Morazán where Parque Chino stood. That is, there was a park within another: the Chino within the Morazán. Some called it Japanese Park. In any case, it was a garden inhabited by desert plains, cobbled passages between the waters, and a lake of occasional lotuses in which ducks and swans swam. Yes: we had our Swan Lake.

The Chinese Park was created in the early sixties, as part of a process of “chinification” of the city that included garbage cans and kiosks in front of the National Theater and the post office. The birds that swam in its waters vanished during the economic crisis of the eighties and the park disappeared a decade later, to highlight the Temple of Music in the middle of the Morazán landscape. This was told to me by Andrés Fernández: the person I know who knows the history of San José best.

To tell

For at least two decades, the Parque Chino was an oasis in the life of the people of San José. Its disappearance reminds us of the loss of many of the spaces that our grandparents conceived for free and joyful recreation. That could be a new definition of oasis: a place conducive to stopping, sharing, breathing and imagining. The loss of these spaces also suggests to us that those who transformed our cities into great centers of consumption have told us “Chinese tales”.

A “Chinese tale” is a false or strange story. An exaggerated and difficult to unravel. They say that we say Chinese tale since Marco Polo returned from the East and wanted to tell everything, the amazing, the impossible and the incredible, in his Book of Wonders (1298). In Guanacaste there is a first cousin of the Chinese tale, the talla, which belongs to the oral tradition and is characterized by its humorous and fantastic nature.

On the other hand, the Chinese Tales (2020) written by Danilo Chong are not at all strange, much less false. Chong composes chronicles in which he recounts stories of his life and the Chinese community of Nicoya: the trips undertaken to visit his grandfather; the first bicycle that arrived in the town; the countryman who became a master of the one-finger blow.

To return

I look at our photograph of the Chinese Park and think about those who live outside the frame chosen by my mother. In the other families looking for the best place to have a portrait, in the children who try to reach the long neck of the swans and in the other twenty-something parents who wear diolene bell-bottoms and shake their hair to the rhythm of Hotel California or Dancing Queen.

Remembering the year of the photo is entering a time of wonder. 1976 was the year of Apple’s founding, the first commercial flight of Concorde, and the launch of VHS. Elvis reached 400 million records sold and NASA revealed that the Martians had sculpted a human face on the surface of their planet. In addition, according to the press of the time, UFOs flew over Costa Rican soil. Sometimes, as the writer Daniel Gallegos said, the past is a strange country.

We live a parallel life in our amazing stories and beloved corners. Those corners live, in turn, in the memory of those who remember them fondly. There are countless recreational spaces and parks that have disappeared from the world but remain among us, on their own terms: they refuse to be tracked by satellites orbiting the Earth, they are immune to profit and surplus value and elusive to searches on Waze, Google Earth and Uber Eats.

I travel to San José, arrive at Morazán and advance among the rows of Australian corks that guarded the Chinese Park of my childhood. I willingly fall into the trap that assures us that all past times were better, and I walk in slow motion, as I always do, anyway, during sailing swans and Martians flying over the surroundings of a red bridge. A red bridge with a hunchbacked that someone installed inside a park, inside a park.