My mom arrived early, as always. Dressed in black, she walked through the doors of the funeral home, searched around but found no one she knew. Don Enrique, a very dear co-worker who worked as a mechanic, had died, and grief was rising in his throat. He sat among other weeping women, wept with them, prayed a rosary, and shared their sorrows.

As he approached the coffin, he noticed that it was wrapped in a Costa Rican flag. An older man, with a face of deep pain, introduced himself as the brother of the deceased. “The colonel is gone, may God keep him in glory,” he sobbed. It was then that my mother understood that she had taken the wrong funeral. “Sparks of the trade,” he says today every time he tells the story, with a smile, as if he were enveloped by the irony of life.

I have always found great tenderness in that mistake. What does it matter who is crying for whom, or whether they are mourning for the wrong person? The crying, in the end, does not stop at these trivialities. You don’t need reasons. And isn’t the reference to the “sparks of the trade” a revelation that my mother’s real job is crying? I am convinced that this is the case.

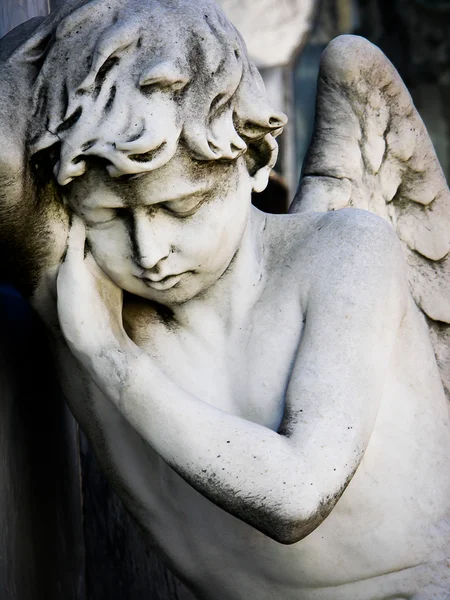

The weeping ones

In ancient times, at funerals, women were hired to mourn. They were called mourners, although the word sounds like an anthropological museum piece. I prefer to call them weeping. What the weeping women did was not acting, but a deep exercise in connection with the pain of others. They lent their bodies and their tears to amplify the mourning of others, as if, by crying together, the pain could become more bearable.

It is said that the weeping women did not follow a plan. They knew, by inheritance or intuition, when to let go of the lament, when to tremble without falling, how to make the voice break at the right moment. Masters of catharsis, their crying functioned as a personal liberation and as a bridge between those who stay and those who leave. It was a silent ritual that honored loss.

As they left our mothers’ bodies, a violent cry merged with weeping. Without that primitive link with the world, which marked the beginning of our life, we would not be here. With their pain exposed, the weeping women teach us that crying is not a weakness, but a sacred act and a return to our first language.

A sentimental education

I grew up, like so many men in Central America, under the mantra that “men don’t cry.” Added to this limit was the constant presence of La Llorona: the ethereal figure that wanders the world, condemned to cry out her sorrow. Thus, since childhood, we were taught to feel fear and to suppress crying. To walk with our losses submerged in the depths.

We also grew up surrounded by melodramas. At the age of eight, I discovered Memín Pinguín, an Afro-Mexican boy, clumsy and noble, with a heart bigger than his clumsiness. Their adventures were told in a weekly magazine, and they taught us that crying could be a path to self-improvement.

At ten, Marco arrived: a television series that was also a continuous reminder of human frailty. In her quest to find her mother, we learned, with Marco, that life can be an unequal struggle. We also learned to look within ourselves.

The characters in melodramas do not cry alone in magazines or on screens; they invite us to share their tears, to feel the pain and to relive the emotion without fear. While life is often presented with the coldness of facts, figures and statistics, melodrama reminds us that, first and foremost, we are beings who suffer and are moved. That they move with others.

A form of love

Crying is present in our daily lives, in conversations that last until dawn, in wordless hugs, in the moments when we face the most painful losses. Crying is, without a doubt, the most honest way to show ourselves vulnerable.

In his Llanto por Ignacio Sánchez Mejías, Lorca reveals that crying can be a form of love and honor. To cry is not to surrender, but to pay homage.

Just like my mom did when she arrived at the wrong funeral: she honored someone she didn’t know. In her generous weeping there was comfort, beauty, and a truth that we rarely reach.

I hope that, when I die, a crying woman will come to my side and accompany me. Let no one ask you if we are relatives or friends. To be allowed to sit, pray, and cry, even if I am the wrong deceased.