After four hours on the road, the bus stopped on a gravel road next to one of those endless pineapple farms in the northern Caribbean. Luckily, it wasn’t pouring with rain, as is almost always the case during the rainy season. There was barely any rain. Armed with an umbrella, just in case, we got off the bus excited because we would finally be talking about geology.

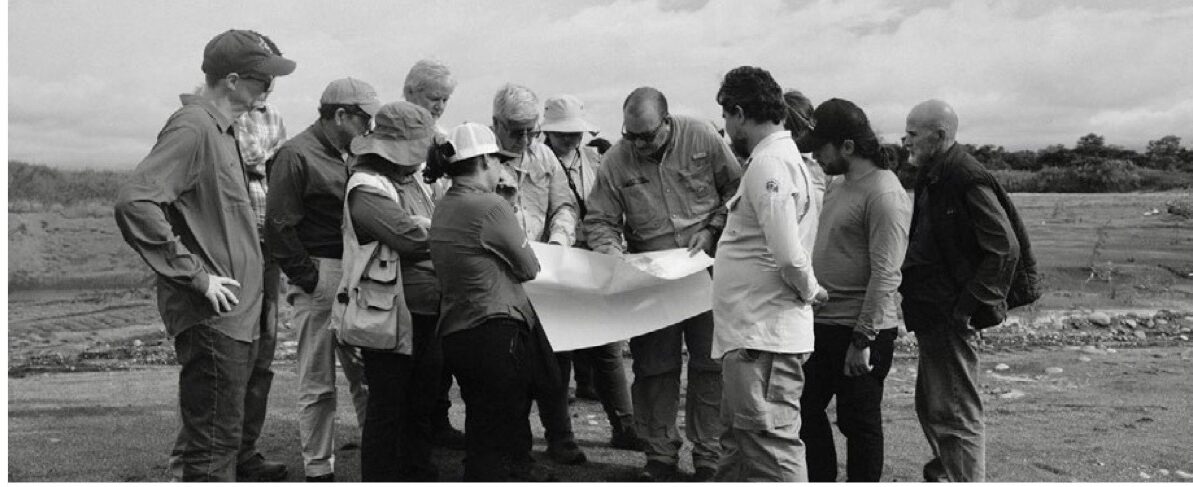

The passengers on the bus formed a circle around the map. Guillermo Alvarado pointed to the spot where we were, about 15 kilometers north of Guápiles. Then he dragged his finger down a dotted line until it met another line showing the Chirripó River. With that gesture, we understood that we were on a road that had once been a river.

Like geologists normally do, we started examining the road and its surroundings for signs of margins, escarpments, and differences between sediment types that would indicate we were on the edge of a river. To our surprise, there were no signs. Everything was flat. The same. We only relied on the map for guidance.

In 1970, instead of flowing northward to join the San Juan River, the Chirripó made a nearly 90-degree turn to the northwest and joined the Sucio River. Thus, overnight, it transformed agricultural and livestock land into the bed of a new river. Why did it decide to change course, travel a greater distance, and cease to be the boundary between Heredia and Limón? Why did it pass on the job of being a border to the road and, in the process, become “Heredian”?

A mega-fan

On the way to Guápiles, on Route 32, after passing through Braulio Carrillo National Park, we saw the liquid embrace of the Sucio and La Hondura rivers. At that point, the natural dirtiness of one mixes with the crystalline appearance of the other.

These rivers have carried enormous amounts of sediment produced by erosion, landslides, and eruptions of the Irazú volcano. When they reach the foot of the volcano, they slow down and deposit these materials in a fan-shaped pattern that spreads out from the point where they touch the plain.

But the Sucio and La Hondura rivers are not the only ones that flow down the northeast side of the Central Volcanic Mountain Range. The Toro Amarillo, Chirripó, and Puerto Viejo rivers, among others, also flow down this area. Therefore, there is not just one fan, but several intertwined fans that form the Santa Clara Mega Fan, which is about 40 km wide and 30 km long.

On the bus, we read a couple of articles about the evolution of the mega-fan, which began to form approximately 14,000 years ago, when the ambient temperature was about seven degrees Celsius lower than today and there was ice on the tops of volcanoes. As the ice melted during eruptions, large mudflows were deposited at the base of the fan. Then, as temperatures rose, rain continued to do its work, carrying more sediment.

One of the articles discussed the recent migration of the Toro Amarillo River, which, since 1960, has shifted almost five kilometers to the west. Today, it is about to converge with the Chirripó River. Thus, it will lose its name but gain strength.

Flow and adapt

Around three in the afternoon, it started to rain. Some of us suggested taking shelter in a bar, where, sitting around the table, we had everything figured out. The way the spilled beer moved was unpredictable and affected by the unevenness of the table and the speed of the liquid. That was probably what happened to the Chirripó River: it changed course when it had to deal with the sediment thrown up by the Irazú volcano in the early 1960s.

The Chirripó continued to flow and adapted to the terrain, even if that meant turning back and taking a longer route to reach the sea. In this way, it defied popular wisdom, which states that only rivers do not turn back. It also abandoned the path laid out for it to join the Sucio River and then the Sarapiquí and San Juan Rivers.

Nomadic groups, such as the Bedouins and Eskimos, have survived for centuries thanks to their ability to move to more stable, more prosperous places. The Chirripó River is also nomadic. It flows freely like liquid spilled on a table. It explores new paths and travels to meet other rivers. It feeds off them and grows stronger. More abundant. It knows that, on its long journey to the sea, the main thing is not to arrive first, but to know how to arrive.