I sit in front of my computer, ready to write. I have decided to travel to Uvita, in the South Pacific, without packing suitcases, hat or sunscreen. I close my eyes and let the memories of a trip I took a few years ago with the family settle in, when we walked on the tail of a whale that the sand had drawn on the beach, in the Marino Ballena National Park.

We advance on that tail at low tide. The sea splits in two and the natural corridor opens, wide at the beginning and narrow later. This strip, made up of sand and gravel carried by currents, connects the coast with an islet that can be seen in the distance. Geologists call it a tombo. A name, certainly, unfortunate for something so beautiful.

The islet is slowly approaching. We are accompanied by the salty air and the echo of the waves that break in parallel. At the end, layers of stone lean towards the beach, grateful that they are not alone, but connected – at least for a few hours a day – to the mainland.

Sitting on those sloping rocks, in the middle of a cemetery of logs and wet sediments, I enjoy the coast loaded with green. Then I orient my body towards the sea. I could stay there for hours, watching the water and its waves.

On the tail of a whale

Immersed in that hypnotic charm, I notice that the waves become more frequent and pronounced. The green of the water darkens, becomes bluer. Suddenly, a roar shakes the air and thousands of droplets cover me, mixed with fish and algae that rain down from the sky. In front of me there is not an islet, but a blue whale that emerges to breathe…

In a moment of lucidity – or madness – I decide to jump and hold on to its tail. It is my opportunity to live a unique adventure: to follow the chain of underwater mountains and volcanoes that form the Coco volcanic mountain range. Of course I depend on the whale route, although I would like to travel the entire route: one thousand two hundred kilometers, from the Galapagos Islands to the subduction zone of Costa Rica.

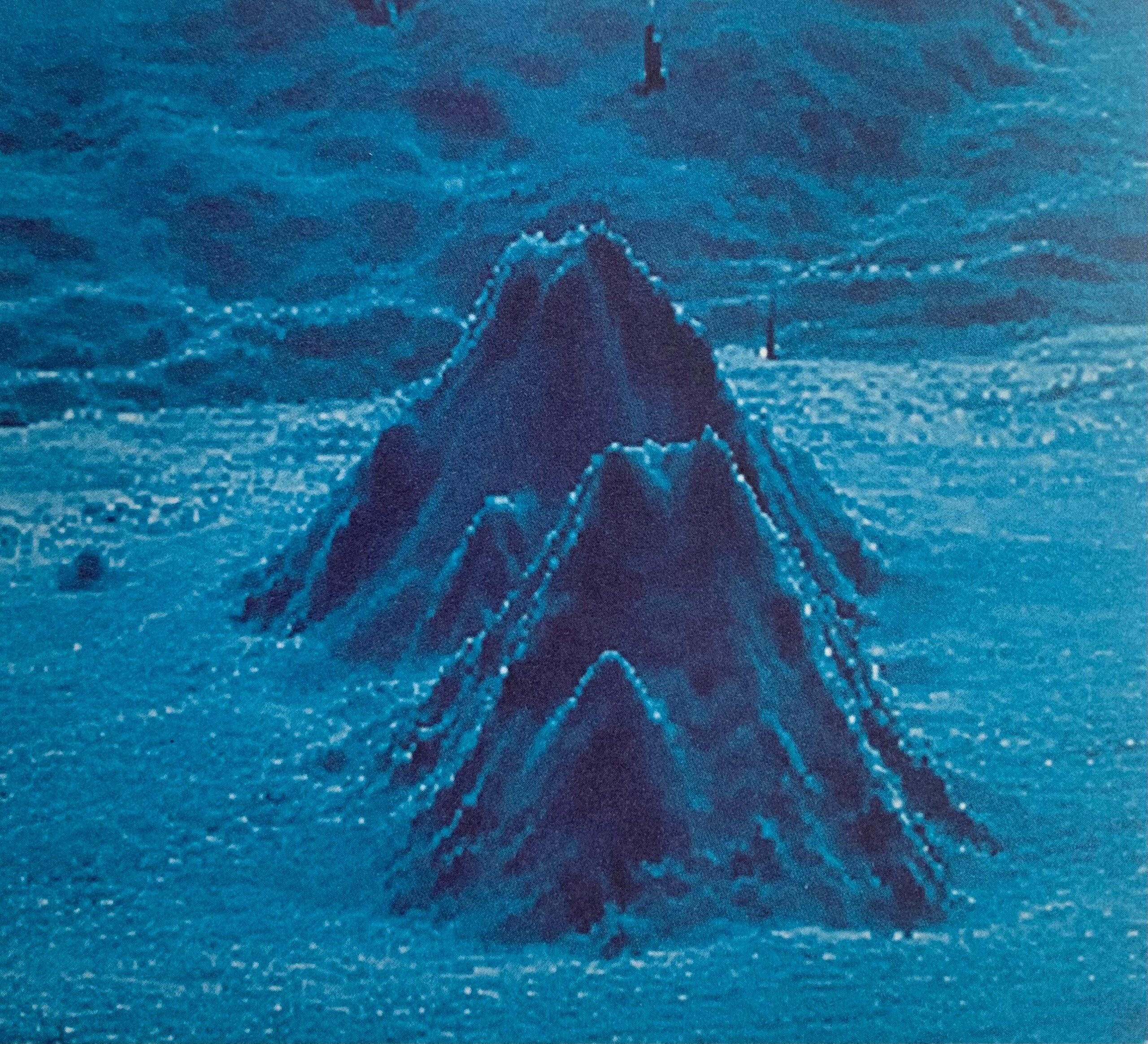

The whale decides to head west, towards the entrance to the Gulf of Nicoya, where the Eva submarine volcanoes rise as Siamese volcanoes. We arrived very quickly. Nothing like traveling by whale, especially when you must dive more than 500 meters below the water level.

These volcanoes have a height comparable to Arenal volcano, but as they are submerged, they do not reach the surface. In addition, they move about 8 cm per year towards the subduction zone, at a rate like that of hair growing. Everything is activity, down there. But since we don’t see it, we don’t know.

It was surprising to see that these volcanoes still retain their craters despite being almost 13 million years old. On land, and especially in the tropics, dormant volcanoes lose their conical shape in less than half a million years due to erosion.

This underwater ridge exists because the Cocos Plate has shifted over millions of years over the Galapagos hot spot, a thermal anomaly in the mantle that functions as an underground torch that won’t go out: an incandescent wound in the mantle that lets magma escape to the surface. As the plate moves over that fixed flame, seamounts are born in sequence, like a path of fire. This is also how the Hawaiian Islands in the middle of the Pacific were formed.

Seeing with different eyes

I look at the Evas, the volcanoes, and I think about my and my daughters’ geography classes, which only included mountains and volcanoes that were above sea level. We don’t learn, nor did we learn, anything about underwater Costa Rica. Our sea is home to about 815 km of the Coco volcanic mountain range, the longest in Central America. The mountain range is named after Cocos Island: its only volcano that emerges above sea level.

Thanks to my whale trip I have managed to see that submerged country with different eyes. Luckily, I had my camera, so I took the opportunity to take a picture of the Evas. Is it always necessary to see things to recognize them?

I think of the Evas and their invisibility that does not make them any less real: on the contrary, they remind us that what is essential is invisible to the eyes, as Saint Exupéry’s Little Prince said. To recognize them is to broaden our idea of territory, to accept that we are also an underwater country. A country that does not end at the coastline: it begins in the path of fire that becomes visible when we close our eyes.