It rained without pause, as if the sky were trying to wash everything clean. Doña Rufina walked barefoot along the steep path, through a night that dragged everything along with it. She had walked all the way from Grifo Alto carrying a lamp wrapped in cloth. The river came down heavy with stones and branches, and lightning lit up the hills as if trying to split them open from the inside.

When she reached the house, the mother was already moaning softly. Her face was pale, her hands cold; her husband boiled water and kept staring at the door, as if waiting for someone else to arrive, though outside there was no one. Only the stubborn insistence of the rain.

Doña Rufina took from her woven bag a Saint Benedict cord, a few rue leaves, and a prayer her own mother had taught her to open the body’s pathways. Then she washed her hands in a bowl of salted water.

The labor was long, but without fright. The child was born whole, strong, warm—but silent. He did not cry. He did not move a hand. His eyes looked at Doña Rufina with an ancient gleam she had never seen in a newborn.

“This one didn’t arrive crying,” she whispered. “This one came seeing everything.”

Then there was a knock at the door. Three times.

“Who is it?” the father asked, but there was no answer.

He stepped out onto the porch and saw him: a man dressed in white, soaked by the rain. His face could not be seen. He said he was looking for shelter, that the river had overflowed and he had lost the path. The father told him to wait, that inside there was a woman in labor. But when he looked again, the man was gone. All that remained was a faint shimmer, a minimal glow, above a trace of freshly disturbed earth.

Doña Rufina cleaned the child with warm water and blew three times over his chest. “So, the soul can settle,” she murmured. She cut the cord, tied it with red thread, wrapped the baby, and placed him beside his mother.

Before leaving, she recited an old prayer—one of those that appear in no book—so that the spirit still wandering in search of a body would not make another mistake.

“That prayer fell into a broken basket,” my grandfather Ramón Ureña would say many years later.

Throughout his life, he dreamed many times of the man in white. He never saw his face, but felt he had known him before. Sometimes he appeared standing in front of the house, other times among the coffee fields or beside a river he could never place. When he woke up, he was certain the dream was neither memory nor nightmare, but a visit.

As an adult, when he worked in Matina, the laborers told similar stories: a man in white who appeared before floods or when someone died far from home. My grandfather listened in silence, and later would say that the same man had been there the day he was born.

Over time he stopped telling the story, as if afraid that naming him would make him leave. As if he might lose the teacher who had taught him to look straight at the visits that had circled him since childhood.

He was about six years old when the witches began to arrive. My grandfather said you heard them before you saw them: they came with faint shrieks, like wet birds, drifting in from the yard as night fell. His mother told him not to go out, not to look toward the chicken coop, but he paid no attention.

The witches were not looking for souls or food, but for air. They wanted the air the boy carried inside him. The breath Doña Rufina had given him at birth. From an early age, my grandfather knew this truth without anyone ever telling him.

That night the dog did not bark, and the hens flapped for no reason. The boy stepped onto the porch holding a kerosene lamp. Behind the coop he saw something moving: a thin, crouched shadow, hair plastered to its face.

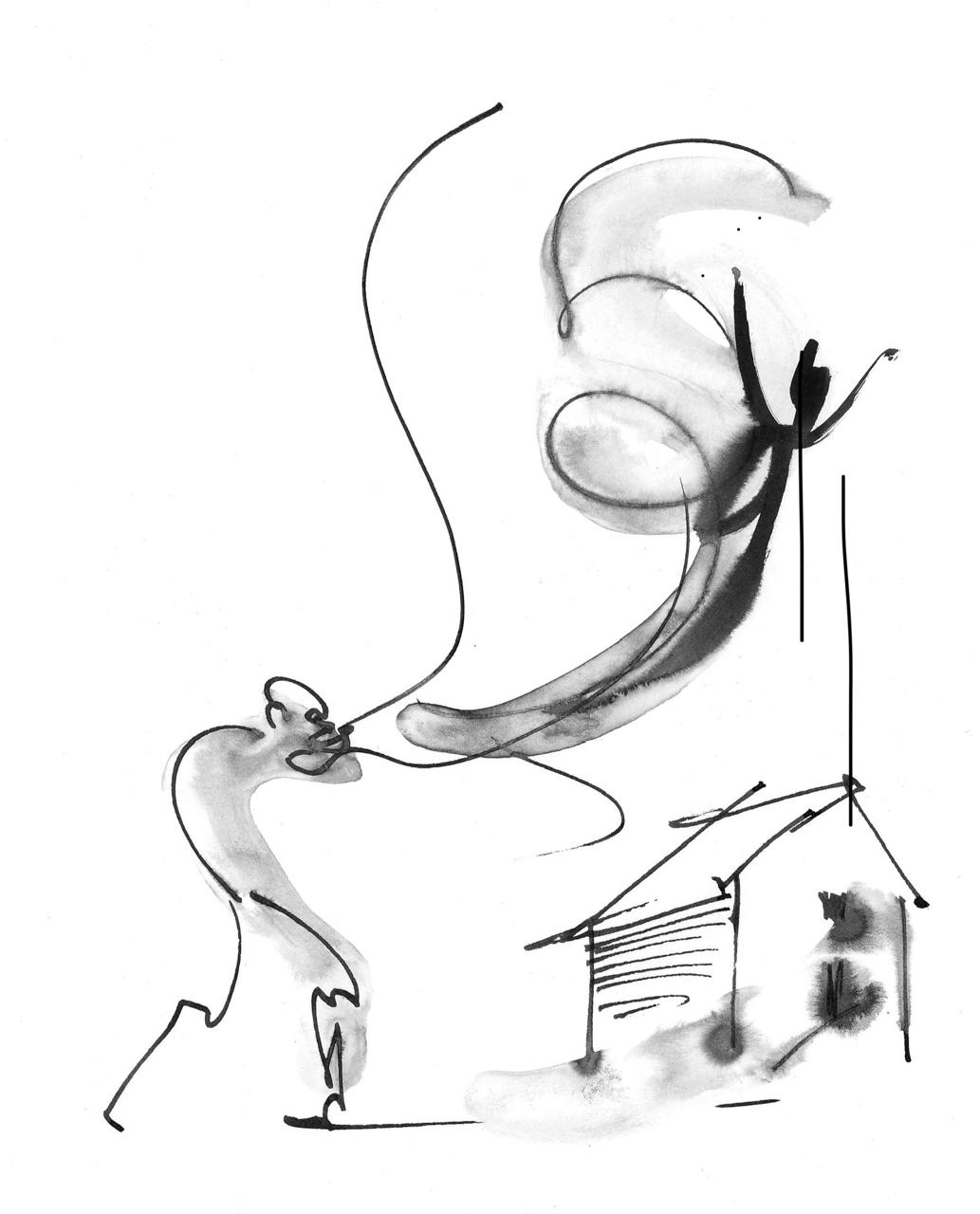

He felt a weight on his chest, a pull outward, as if his air were being stolen. Then he remembered Doña Rufina’s gesture, mimicked the movement, and blew with force. The lamp’s flame bent, and the air turned warm. The shadow recoiled, undone by the wind.

From that day on, on rainy nights, the boy hung the lamp by the window—not to light the way, but to keep the air from falling asleep. They say the soul breathes too, even without a body. Perhaps that is why my grandfather always guarded that first breath as one protects a live ember.

More than a century later, the story still reaches me from time to time, in fragments. When I think of my grandfather, I see his long arms, his hands marked by the machete, and I see him blowing into the darkness. The air leaving his mouth crosses the years and brushes against me. And I understand: the breath was not meant to scare away ghosts, but to keep them close, without letting them hurt.